It’s an absolute thrill to be nominated for this. Congratulations to our Shadows team and fellow nominees!

“It was fascinating working on those montages with David [Lynch.] Now by doing it with video, it would be easier to get inside his mind, but it was very difficult on film because he didn’t know exactly what he wanted until he saw it. Something complicated like the mother and the elephant we did hundreds of times before we got it right. David would be telling us what he wanted, my assistant was very patient and kept ordering it over and over again, and it was always wrong.”

From Selected Takes: Film Editors on Editing by Vincent LoBrutto

Not surprising to read that Lynch fixated on these montages. He had served as his own editor on Eraserhead and the opening montage to The Elephant Man feels very much a part of that world: dreamlike imagery scored with an industrial soundtrack. That opening can be viewed courtesy of StudioCanal who have put the first 10 minutes of the film on YouTube in order to promote their recent 4K UHD release.

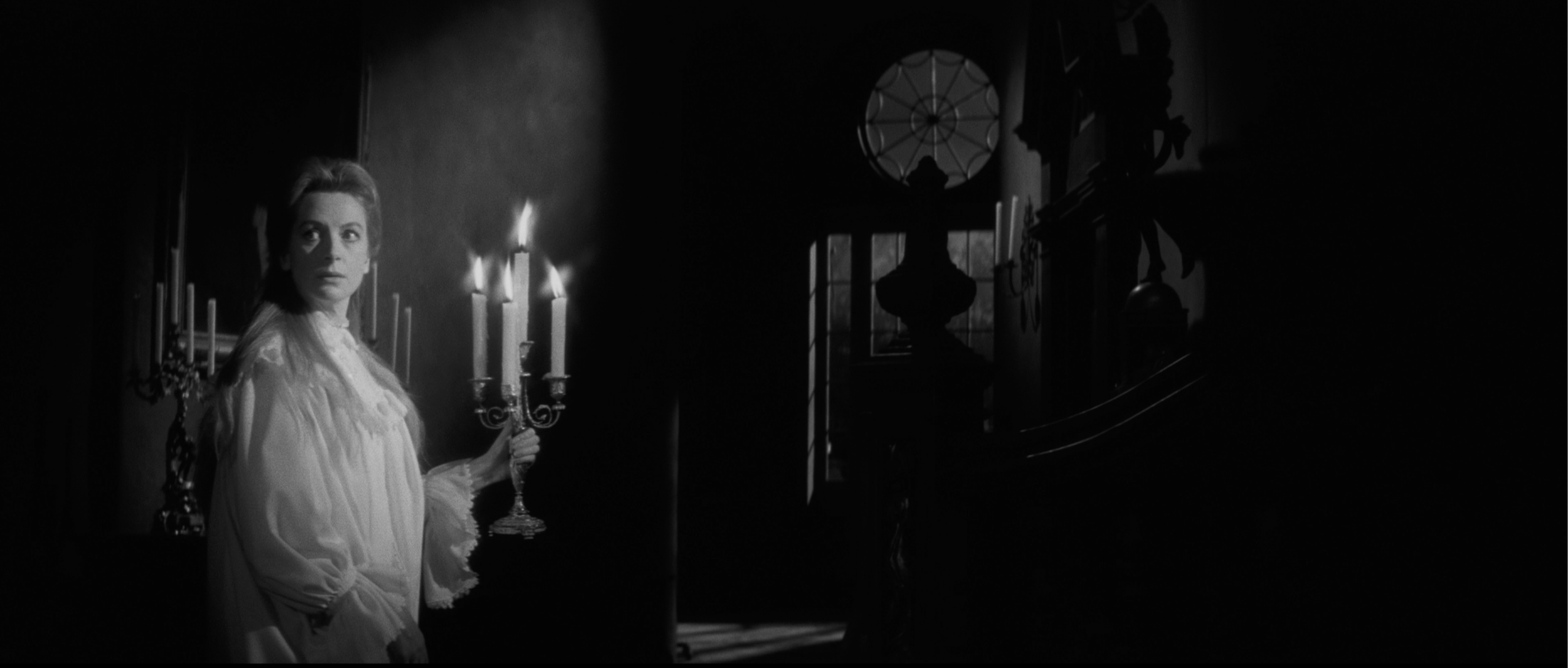

The Innocents is Jack Clayton's 1961 film adaptation of Henry James' The Turn of the Screw. It features a screenplay co-written by Truman Capote, an incredible performance by Deborah Kerr (Black Narcissus), photography by Freddie Francis (The Elephant Man), and - surprisingly - moments that remain genuinely shocking, even 50+ years after its release. It's one of those forgotten films that frequently appear on top horror lists by critics and filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese and Guillermo del Toro. It's also a film that's particularly notable for the editing by Academy Award winner Jim Clark.

Jim Clark’s work on The Innocents features a number of standout moments. The film opens on 45 seconds of black, with just the sound of a creepy children's song - “O Willow Waly” - used to establish an unsettling tone. The main titles feature ambiguous imagery shot at night accompanied by the audio of birds chirping in the day. And the scares are edited in an unconventional pattern throughout: rather than first seeing a ghost, then cutting to an actor’s reaction, here the formula is reversed so that first we see the reaction, then we see the scare.

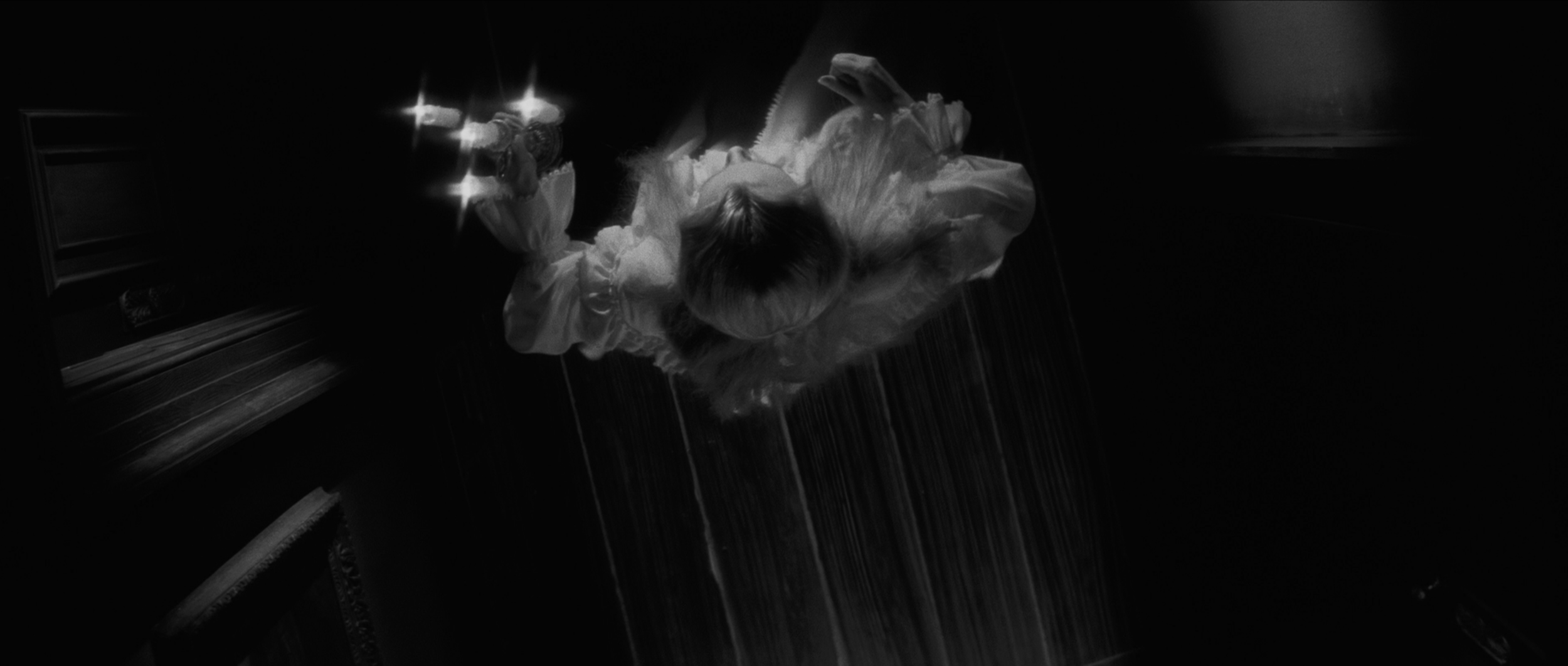

But perhaps the most memorable aspect of the editing is the use of extremely long dissolves and superimpositions. These are scattered throughout the film, beginning with a long dreamlike dissolve that takes us out of the main titles and into the opening scene, and culminating midway through the picture in a stylized sequence that displays this technique to stunning effect:

The editing combined with Freddie Francis’s photography and some wonderfully creepy sound design produces a haunting otherworldly collage. Fragments of images linger at the tail ends of dissolves, producing ambiguous ghost-like shapes and textures. And this was done at a time when executing such an effect was no easy task. Here's Jim Clark from Criterion's special feature The Making of The Innocents:

"When it came to the montage of long dissolves and super impositions, that was the first time that I had experience of that kind of scene. And therefore I had to invent a way of doing it.

I had the elements that Jack had shot and the only way I could work it out and supply the optical house with some form of template was by cutting it with blank film. I used spacing - what we called spacing - which was blank film. There was no image on it. What I would do was get the piece of film that had the image on it. That was the piece I wanted to use. And I would write the edge numbers on a piece of blank film with the slate number so that what we ended up with were four rolls of film which had no images on them but had numbers written on them. And indications of how long those shots should remain on the screen. So that you would find that you have a superimposition followed by a dissolve. Sometimes you had four images running simultaneously. Other times you had two.

The laboratory and the optical house were quite bemused by this. They’d never been faced with anything like this before. Although, of course, montages had been around for years. In Hollywood, particularly."

And here's Clark from his autobiography, Dream Repairman: Adventures in Film Editing:

"I was also able to indulge in some rather cunning dissolves, somewhat influenced by George Stevens’ A Place in the Sun. These would not be simple mixes of equal length. A 4-foot mix is the norm, but these would last 15 or 20 feet, the images gradually merging. I referred to them as lopsided mixes since the overlaps were nonstandard and often there would be a third image in there too, so these mixes were like mini montages. I didn’t always get them right the first time, and the optical house had its problems, but the results were very pleasing to Jack and myself."

In order to translate the above into modern non-linear editing terms, I had to look up the ratio of 1 foot of film in relation to frame count:

- 16mm :

40 frames per foot

36 feet per minute at sound speed (24fps)

- 35mm : (4-perf)

16 frames per foot

90 feet per minute at sound speed (24fps)

Therefore:

- 4 Foot Dissolve: 64 Frames / 2.7 Seconds

- 15 Foot Dissolve: 160 Frames / 10 Seconds

- 20 Foot Dissolve: 320 Frames / 13.3 Seconds

As an editor, I've always been wary of using dissolves. "If you can't cut it, dissolve it," as the saying goes. With the exception of fading to or from black its been years since I've applied one. But Jim Clark's work on The Innocents makes me want to experiment with superimpositions and 13 second dissolves at the first available opportunity.

Purchase The Innocents.

John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands reviewing footage in their home garage in Hollywood. I wish I could accurately pin down the date of this picture to identify what film they're working on, but the internet provides conflicting information.